Flow • Mihaly Czikszentmihalyi • 1990

On Flow and Cultivating Complexity

In Short

Flow activities are desirable because they draw us through a cycle of developing higher levels of skill and attempting more challenging tasks, which pushes us to develop a more complex sense of self.

In Depth

The result of experiencing flow, according to Csikszentmihayli, is the emergence of a more complex sense of self. In every instance of flow he has studied, it “pushed the person to higher levels of performance, and led to previously undreamed-of states of consciousness” (p. 74).

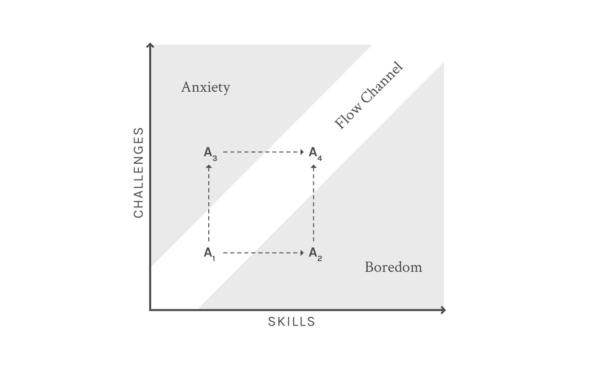

Csikszentmihayli uses the following visual model to illustrate this idea.

The axes of the graph represent the challenge level of the task in front of a person and the skill of that person. At the outset of the experience, they start at A1 where they don’t have much skill in performing the task, but they are also taking on simpler challenges.

One of two things happen at this point: they may either get better at the task or the task starts to get harder. If they get better at the task, their skill level goes up (A2). If the challenge of the task hasn’t increased to match their increasing skill, they will likely get bored with the task (represented by the bottom triangular area of the graph), breaking their flow state.

If the challenge level of the task has increased (A3), but their ability to perform it has not, then they start to feel anxiety about their performance (represented by the top triangular area on the graph), also a negative emotion that disrupts flow.

In either case, a proper flow activity finds ways to self-correct and push the person back into a flow state where their skill level is perfectly matched to the challenges they are facing (represented by the “Flow Channel” on the graph).

If bored, the person is likely unable to reduce their skill level after having improved it, so they are pushed to attempt more challenging tasks (from A2 to A4).

If anxious because the challenge of their task is too much, they are motivated to increase their skill (from A3 to A4). Theoretically, they could also go back to simpler challenges, but Csikszentmihayli points out that, in practice, it’s difficult to be satisfied with lower level challenges once you’ve been made aware of higher levels.

This pattern continues, alternating between the development of higher skills and the attempt of more difficult challenges, to push the person to greater complexity of self. Csikszentmihayli connects this idea of complexity to various models of self-improvement and meaning-making.

...most theories recognize the importance of this dialectic tension, this alternation between differentiation on the one hand and integration on the other… Complexity requires that we invest energy in developing whatever skills we were born with, in becoming autonomous, self-reliant, conscious of our uniqueness and of its limitations. At the same time we must invest energy in recognizing, understanding, and finding ways to adapt to the forces beyond the boundaries of our own individuality. (p. 223)

It’s a neat model that speaks well to an interactive medium. It suggests a way to design something that encourages growth by adapting to the person using it over time or progressively revealing layers of complexity and meaning the more they use it.

Though, Csikszentmihayli offers one warning to avoid taking the model as a sure-fire formula for enjoyable experience.

It is important, however, not to fall into the mechanistic fallacy and expect that, just because a person is objectively involved in a flow activity, she will necessarily have the appropriate experience. It is not only the “real” challenges presented by the situation that count, but those that the person is aware of. (p. 75)